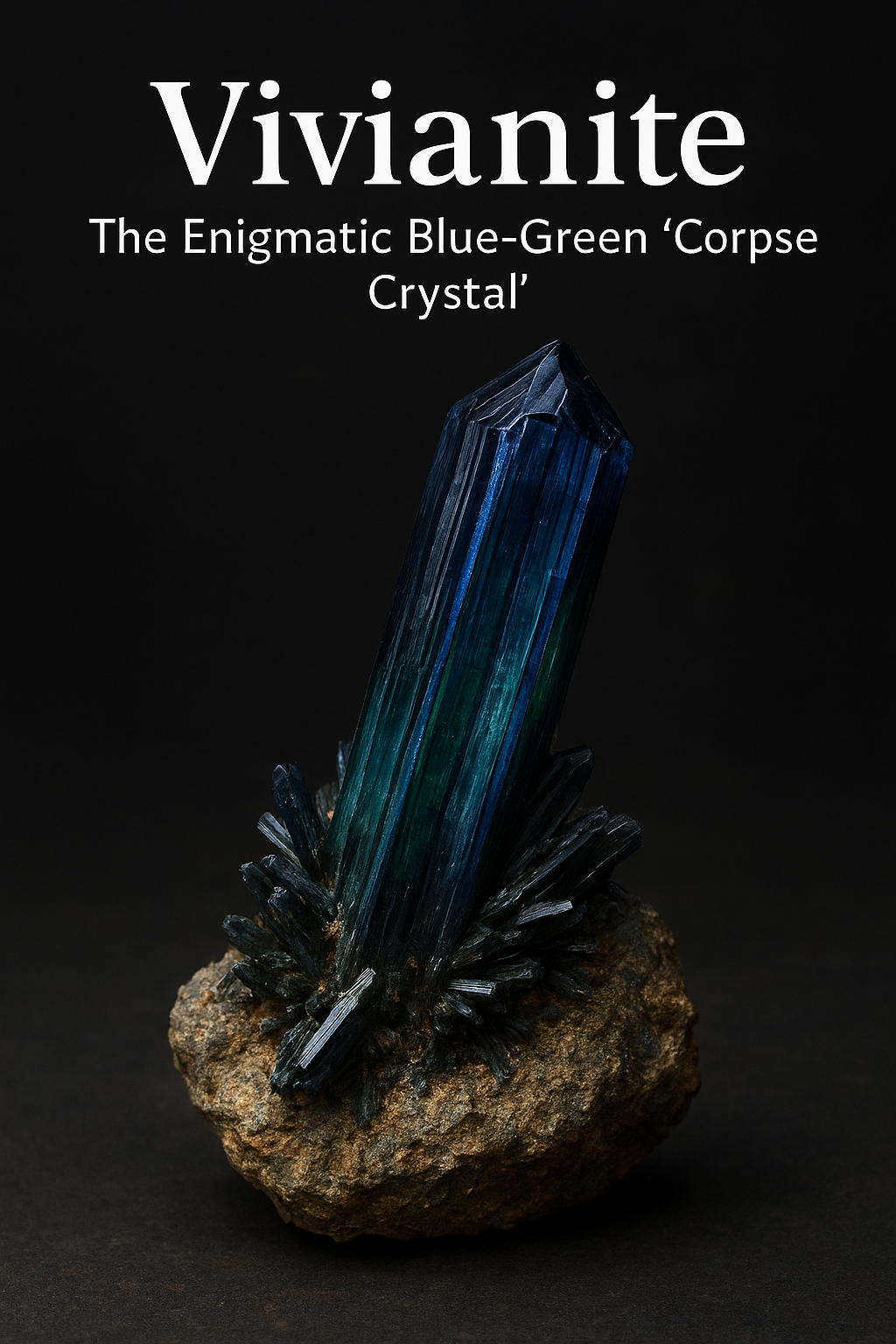

Vivianite: The Enigmatic Blue-Green Mineral That Changes with Time

Vivianite is one of the most intriguing and visually captivating minerals known to collectors and geologists alike. Famous for its vivid blue-to-green hues and remarkable tendency to darken upon exposure to light, Vivianite is both scientifically fascinating and aesthetically enchanting. Though relatively soft and delicate, its translucent beauty and transformative nature make it a prized specimen in the world of mineralogy.

1. Introduction to Vivianite

Vivianite is a hydrated iron phosphate mineral, with the chemical formula Fe₃(PO₄)₂·8H₂O. It belongs to the vivianite group, which includes minerals like metavivianite and baricite. Named after John Henry Vivian (1785–1855), a British mineralogist and politician, it was first described in 1817 from Cornwall, England.

What makes Vivianite especially unique is its color transformation. Freshly exposed crystals are colorless to pale green, but they quickly oxidize, turning deep blue, indigo, or nearly black as iron(II) oxidizes to iron(III). This property symbolizes its constant state of evolution—almost as if the mineral were alive.

2. Chemical Composition and Structure

- Chemical Formula: Fe₃(PO₄)₂·8H₂O

- Mineral Class: Phosphate

- Crystal System: Monoclinic

- Crystal Habit: Typically forms as elongated prismatic or tabular crystals; can also appear fibrous, massive, or earthy.

- Cleavage: Perfect on {010}

- Fracture: Uneven to splintery

- Mohs Hardness: 1.5 – 2

- Specific Gravity: 2.68 – 2.71

- Luster: Vitreous to pearly

- Transparency: Transparent to translucent (darkens to opaque when oxidized)

Vivianite’s structure consists of Fe²⁺ cations bonded to phosphate anions and water molecules. The hydrated structure gives the mineral its relatively low hardness and sensitivity to environmental changes, including humidity and light exposure.

3. Color Transformation and Light Sensitivity

One of the most striking characteristics of Vivianite is its photo-oxidation process:

- Fresh Vivianite: Usually pale blue, bluish-green, or colorless.

- Exposed Vivianite: Gradually turns deeper blue, green-blue, or black as oxidation occurs.

This color change is due to the oxidation of Fe²⁺ (ferrous iron) to Fe³⁺ (ferric iron). During this transformation, the crystal structure slightly alters, affecting how light interacts with the mineral’s surface. Over time, heavily oxidized Vivianite can become nearly opaque, resembling black tourmaline.

Collectors often store Vivianite in dark, airtight containers or display cases with UV-blocking glass to preserve its original coloration.

4. Formation and Geological Occurrence

Vivianite forms in low-temperature, reducing environments, often associated with organic material and iron-bearing sediments. Its formation requires conditions where iron and phosphate ions can combine in the presence of water and little oxygen.

Common Formation Environments:

- Sedimentary deposits: Especially in clay, marl, and peat bogs where organic decay provides phosphate.

- Fossil and bone cavities: Vivianite often forms as blue-green coatings on fossil bones or shells, replacing organic phosphate materials over time.

- Hydrothermal veins: Rarely, it can occur in association with sulfide minerals.

- Weathering zones: Forms as a secondary mineral in iron ore deposits and phosphate-rich environments.

5. Notable Localities

Vivianite occurs worldwide, but only a few localities produce well-crystallized, collector-grade specimens.

- Bolivia: Santa Rosa Mine (Potosí) – Famous for stunning deep blue to green transparent crystals, often growing in radiating clusters.

- Germany: Horhausen, Rhineland-Palatinate – Classic European source, known since the 19th century.

- USA:

- New Jersey: Notable for fossilized bone nodules containing Vivianite.

- South Dakota: Found in the Black Hills, often as green coatings in lignite.

- Florida & Alaska: Occurs in bog iron deposits.

- Russia: Kerch Peninsula and Siberia – Produces fine, large crystals.

- Australia: Queensland – Noted for striking blue-green crystal sprays.

Each locality can influence the mineral’s appearance—Bolivian crystals, for example, tend to be deeply colored and transparent, while those from sedimentary deposits may appear earthy and fibrous.

6. Associated Minerals

Vivianite is often found alongside minerals such as:

- Pyrite (FeS₂)

- Siderite (FeCO₃)

- Apatite (Ca₅(PO₄)₃(F,Cl,OH))

- Quartz (SiO₂)

- Metavivianite (oxidized form)

- Chalcopyrite, Limonite, and other iron oxides

In organic-rich sediments, it frequently appears with fossil remains or in phosphate nodules, giving paleontological specimens a distinctive bluish-green sheen.

7. Identification and Testing

Vivianite can be identified by:

- Color and pleochroism: Light blue to deep blue-green depending on orientation and oxidation state.

- Softness: Easily scratched with a fingernail.

- Reaction to light: Gradual darkening when exposed.

- Solubility: Slowly soluble in acids.

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) or Raman spectroscopy confirm its phosphate composition.

Because of its softness and fragility, Vivianite must be handled carefully. Even gentle cleaning or long-term display lighting can damage or darken the specimen.

8. Uses and Value

While too soft for jewelry, Vivianite is highly prized among mineral collectors and museums for its color, rarity, and transformative qualities. In geology and paleontology, it serves as an indicator of reducing, phosphate-rich environments—helping scientists reconstruct sedimentary and fossilization conditions.

Fine Bolivian specimens, with transparent, deep-blue crystals, can command significant value, especially if unaltered and well-preserved.

9. Care and Preservation

To maintain Vivianite’s beauty:

- Avoid direct sunlight or strong artificial light.

- Store in a sealed, dark container with minimal humidity.

- Do not clean with water or chemicals.

- Handle with gloves to prevent oils from altering the surface.

Some collectors coat Vivianite in thin layers of clear acrylic or display under dim LED lighting to slow oxidation.

10. Metaphysical and Symbolic Meaning (Optional Perspective)

Though not a primary scientific aspect, many enthusiasts attribute metaphysical meanings to Vivianite. It is said to:

- Encourage compassion, healing, and self-awareness.

- Open the heart chakra and promote emotional clarity.

- Inspire transformation—symbolizing its real-life ability to change color with light.

Whether viewed scientifically or spiritually, Vivianite’s dual nature embodies transformation, introspection, and renewal.

💀 Why Vivianite Is Called the “Corpse Crystal”

Vivianite earned its nickname “the corpse crystal” (or sometimes “death crystal”) because it has been found growing on human remains, particularly in burial sites, bogs, and graves, where the conditions are ideal for its formation.

Here’s how and why this happens:

1. Vivianite Forms in Low-Oxygen, Organic-Rich Environments

Vivianite requires:

- Iron (Fe²⁺)

- Phosphate (PO₄³⁻)

- Water

- Low oxygen (reducing) conditions

In a burial environment, all of these are present:

- Iron often comes from the soil or coffin nails.

- Phosphate is released from decomposing bones and soft tissues.

- The environment is moist and oxygen-poor, especially in peat bogs, clay, or waterlogged soil.

Over time, these ingredients combine to form Vivianite crystals directly on bones or in the surrounding soil.

2. The Color Change Makes It Even More Macabre

When freshly formed underground, Vivianite is colorless to pale green.

But once the grave is disturbed or excavated and the mineral is exposed to air and light, it oxidizes and turns deep blue, green-blue, or almost black.

That eerie color shift—from pale to dark blue—has been poetically compared to the “blueing” of decaying flesh, strengthening the association with death and decomposition.

3. Archaeological Discoveries Cemented the Nickname

Archaeologists have documented Vivianite forming on skeletal remains and within coffin sediments in burial sites around the world, including:

- Medieval and prehistoric graves in Europe

- Waterlogged archaeological sites in England, Germany, and Russia

- Peat bog burials, where the preservation of organic matter allows the mineral to thrive

In some cases, entire skeletons or burial chambers were tinted with a ghostly blue-green hue from Vivianite growth.

This phenomenon fascinated both scientists and the public—leading to its morbid but memorable nickname:

👉 “The Corpse Crystal.”

4. Scientific Importance

Beyond the nickname, these occurrences are valuable to researchers.

Vivianite formation in burial contexts helps archaeologists:

- Determine soil chemistry and preservation conditions.

- Understand the taphonomic processes (how remains decompose).

- Infer environmental and burial conditions at the time of interment.

5. Symbolic and Cultural Associations

The eerie transformation and connection to the dead have also inspired spiritual and artistic interpretations.

Some people view Vivianite as a symbol of transformation, rebirth, and the cycle of life and death, since it literally emerges from decay and changes color over time—reflecting nature’s continuous process of renewal.

🧬 In Summary

Vivianite is called the “corpse crystal” because it:

- Forms on bones and remains in burial environments rich in iron and phosphate.

- Changes color upon exposure to air, mimicking the blue hues of decomposition.

- Has been discovered in human graves and bog burials, giving it a direct connection to the deceased.

What began as a scientific curiosity became one of mineralogy’s most poetic—and haunting—nicknames.

Conclusion

Vivianite stands out as one of nature’s most dynamic and mesmerizing minerals. Its delicate structure, stunning colors, and ever-changing appearance make it both a challenge and a reward for collectors and geologists. Each crystal tells a story of transformation—from iron-rich sediments to gleaming blue prisms that evolve with time.

From museum exhibits to private collections, Vivianite continues to captivate all who encounter its mysterious, living beauty—a mineral that truly changes before your eyes.

© 2025 Gems and Minerals Rock

All rights reserved. This article may not be reproduced without permission.